BLOG

Each week we will upload extracts of the academic papers published throghuout the years

1

TO GAUGE AN UNDERSTANDING OF HOW BOUNDARIES ARE PERCEIVED IN IRELAND BY LANDOWNERS - FIG 2011

SUMMARY

Recent anecdotal evidence from property professionals indicates that there has been a significant increase in boundary disputes in Ireland since the phased publication of the Land Registry digital map in 2005. There is a need to investigate this development in order to confirm or refute this trend and attempt to identify the issues causing these disputes. There is an absence of detailed information on the causes and types of boundary disputes within the Irish Legal system. This project aims to address this lack of information by collecting comprehensive information on a range of case studies over the past 5 years and determine the incidence of these types of disputes. The cost to all parties to these disputes will also be estimated to inform policy makers of the effectiveness of the current system. An electronic questionnaire on boundaries in general, was carried out to gauge the perception and context in which property boundaries are perceived in Ireland by landowners. Initial results from this first questionnaire show that 32% and 38% of landowners in urban and rural areas respectively have issues with their boundaries, and 22% of landowners did not know whether their property is registered in Land Registry (Now know as Tailte Eireann) or in Registry of Deeds. A second questionnaire, currently in progress, intends collecting information on specific boundary dispute cases to determine the issues causing these disputes and identify the various types of disputes within this litigation category. This study hopes to inform the need for policy reform of the Land Administration System for land tenure in Ireland.

(Blog post added 04/08/2025)

To gauge an understanding and concept of how boundaries are perceived in Ireland by landowners (est. 2011)

Daragh O’Brien

1. INTRODUCTION

Without boundaries there would be no maps. International boundaries have been man made which give countries their shape and whose borders limit sovereignty. Boundaries were formed throughout history based on historical background and colonial times. Where you find boundaries a detailed analysis may uncover conflict, whether this is between one country and another, it is very prevalent between one landowner and another. The purpose of this paper is to show Irish landowner’s knowledge of their boundaries and an overall perspective of how property boundaries

are perceived in Ireland.

Many landowners know where their property boundaries are by locating the physical features on and around their holding. However, ask them to precisely identify where the exact boundary lines are, many have different views where their boundaries are. Their views range from identifying the physical natural boundary, locating deeds, maps, architectural/engineering/land surveying drawings or they may not know at all. Detailed and specific information is not available for Irish property owners and maybe inadequate for use today in mapping or conveyancing. Information on boundaries needs to be clarified and accurately defined to avoid ambiguity. This paper includes a detailed discussion of the key findings from two questionnaires and concludes with a number of recommendations.

(Blog post added 11/08/2025)

2. BOUNDARY CATEGORIES

The term boundary is denoted by a physical feature marking the limit of a land parcel or an imaginary line identifying the divide between two legal interests in a plot of land (Williamson et al, 2010). The boundary system within a country is the cornerstone for a land administration to work effectively and efficiently. Below is an example of some of the main categories of boundaries.

2.1 Cadastre

Recording and taxing ownership of land has been in operation since Egyptian and Napoleonic times. Cadastres were one of the first systems used to aid in the collection of taxes on land. A Cadastre can be described as a complete co-coordinated map of accurately defined land parcels, which describe every parcel of land in a country i.e. residential properties, commercial properties, roads, public spaces and infrastructure (Wallace et al, 2010). Cadastres are planimetric maps where accurate co-coordinated measurements of boundaries can be taken from the map. No topographic features are shown on Cadastre maps. An important requirement of Cadastral maps is that they show a sufficient number of points, which can accurately define positions on the ground (FAO, 2011). In most countries, ground surveys are used to accurately define the land parcels. However, some countries cannot afford to survey land parcels on the ground due to expenses involved and lack of personnel. Once a Cadastre is functioning, detailed information can be accessed from the maps including the ability to scale information (Wallace et al, 2010). All this information is stored in digital databases where geocoding is added i.e. street address, location of houses and plot numbers etc. A country that uses a cadastre efficiently is Australia where farmers, developer’s, water authorities, road builders, delivery systems, planners, land managers and others use this system which provides information and data to them in an authoritative and legally enforceable way (Wallace et al, 2010). A Cadastre system is essential for a good land administration and land management.

(Blog Post added 18/08/2025)

2.2 Conclusive Boundaries

Conclusive boundaries are also known as fixed boundaries. Conclusive boundaries were introduced under the Torrens system where property boundaries were guaranteed when ones land was registered (Murphy et al, 1992). Conclusive boundaries can be defined as the precise line of the boundary determined by land surveys which are in turn expressed by co-ordinates (Williamson et al, 2010) where as the Inter-Professional Task Force on Property Boundaries (IPTFPB) defines a conclusive boundary as where, “…the register does contain sufficient information to define the boundary either legally or geometrically so that it is not open to challenge, and is guaranteed by the state” (IPTFPB, 2010). Concrete posts, steel rods or a boundary mark in the ground usually represents these types of boundaries marked by professional surveyors. This boundary system is the most common system used around the world and two variants are available, the German and Torrents systems (Figure 3).

(Blog Post added 25/08/2025)

2.3 Non – Conclusive Boundaries

Non-conclusive boundaries are also known as general boundaries in the United Kingdom. Ireland uses a non-conclusive boundary system where the precise location of the boundary and its features is not accurately defined. The system is defined as where,

“…the register does not contain sufficient information to define the boundary either legally or geometrically. Consequently, the boundary is open to challenge, and is not guaranteed by the state” (IPTFPB, 2010).Ireland began to use non-conclusive boundaries in 1891 under the local Registration of Title Act, which came about from the English Land transfer Act 1875. More recently in the Registration of Title Act 1964, S85, it states,

“…except as provided by this Act, the description of the land in the register or on such maps shall not be conclusive as to the boundaries or extent of the land” (Houses of the Oireachtas, 1964, Section 85).

Irelands land registration system is made up of folios and maps. Irish property folios are deemed to be reliable, thus the title is conclusive and guaranteed by the state. In contrast, the Property Registration Authority (PRA) (now known as Tailte Eireann) maps are regarded as unreliable and non-conclusive and are consequently not guaranteed by the state. This aspect of the Irish mapping system is less secure and is an area where reform is needed (Prendergast el al, 2008). Non-Conclusive boundaries are usually represented on the ground by physical features, natural or man made, for example, fence, hedgerow, wall, ditch, road or tree line (Williamson et al, 2010). It should also be noted that the registered boundary depicts the physical feature rather than the determined boundary.

(Blog post added 02/09/2025)

3. Irelands Property Boundaries

Ireland has two separate systems for recording property transactions, the Registry of Deeds (registration of deeds system) and the Land Registry (registration of title system). The first system of registration was introduced in 1707 when the Registry of Deeds was set up to record the registration of documents dealing with land and conveyances under the Registration of Deeds Act of 1707 (Fitzgerald, 1989). There was no obligation to register, however priority was lost in failing to register and thus it became standard conveyancing practice to register deeds in relation to unregistered land (Fitzgerald, 1989).

Work within the Registry of Deeds became technical and difficult because of the complications with Irish titles and names of town lands, which became time consuming and expensive with fees ranging from £37 – £5,000 for each transaction and reform of the Registry of Deeds was required (Murphy et al, 1992). Reform was being considered in 1854 when the Registration of Title Commission was appointed and on foot of their report in 1857 the Registration of Titles in Ireland was founded.

(Blog Post added 15/09/2025)

In 1858, Irish born Sir Robert Torrens introduced a simple form of registration of title in Southern Australia. The Torrens system was revolutionary delivering cost effective and quick land registration where it detailed on one single piece of paper the description of the land parcel, the known registered proprietor and any encumbrances (i.e. mortgages) to do with the land (Williamson et al, 2010). Ireland adopted the English version of the Torrens system, which in contrast used a form of general boundaries instead of defined boundaries. As Ireland was under British rule at this time, further English acts were implemented and revised, such as The Land Registry Act (1862) and the Land Transfer Act (1875) that after many years of consultation concluded that boundaries were no longer required to be accurate to the nearest inch (Murphy et al, 1992). Various commissions and reports were introduced to deal with registration to develop a satisfactory system for Ireland.

In 1862, an act to facilitate proof of title was introduced to register land, which was voluntary and proved a problem, as only a small number (349) of properties were registered mainly because of the complexity of English law (Murphy et al, 1992). In 1865, land registration was attempted with the Record of Title Act (Ireland) drafted by Sir Robert Torrens, which required land registration within seven days of purchase. This again was cumbersome and slow where only 681 titles were recorded (Murphy et al, 1992). A further Royal Commission issued a report in 1879 and was followed by the Land Law Ireland Act of 1881. The Purchasing Land Act of 1885 recorded 21,850 properties being vested in tenant purchasers (Murphy et al, 1992). The Land Commission was established in 1885 to distribute loans to farmers under a tenant purchase scheme. Substantial progress was made in 1888 when the Attorney General for Ireland suggested two bills to the chief secretary to resolve Land Registry…a) The reform of the Registration of Deeds and b) a Registration of Title. The Registration of Title Ireland bill of 1891 was passed and came into operation on the 1st January 1892 (Murphy et al, 1992).

(Blog Post added 24/09/2025)

When the Land Registry was set up in 1891, Ireland was still recovering from the famine in the 1840’s. Under a British incentive the land registration system was to give tenant farmers freehold ownership of their farms and to replace the feudal system that was in operation at the time (Prendergast el al, 2008). The 1891 Act was amended by the Registration of Title Act 1942 which were both replaced by the Registration of Title Act 1964 and which was then in turn replaced by the Registration of Deeds and Title Act 2006. Most recently in 2009, the Land and Conveyancing Law Reform Act was established to repeal enactments that were obsolete, unnecessary and of no assistance in modern circumstances (Houses of the Oireachtas, 2009).

The Land Registry make it clear that when a map is submitted for registration, it is the responsibility of the applicant to ensure the accuracy of the areas and that boundaries have no conflict with the current Land Registry map (Fitzgerald, 1989). According to Maltby (2010), the lines on a Land Registry map have no spatial significance and simply serve to indicate the separation between properties. The Land Registry also maintains three registers relating to the ownership of land and appurtenant rights on the land, namely freehold, leasehold and hereditaments or other rights on the property.

Each of these consists of separate folios/files that contain information on the title of a particular interest in freehold land, leasehold interest or incorporeal rights which is attached to property and which is inheritable (Brophy, 2003). Nowadays the Registry of Deeds deals with titles mostly in urban areas, while the Land Registry deals with titles outside the main urban areas. Files in the Registry of Deeds record the name of the person who has disposed of property, which or may not have been the property’s owner (Brennan et al, 2008).

(Blog Post added 01/10/2025)

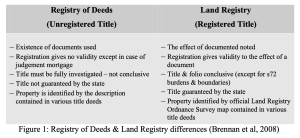

One of the main differences between the Land Registry and Registry of Deeds is that

the Registry of Deeds system provides for the registration of documents dealing with land. The Land Registry provides registration for ownership and title together with other interests in land (Fitzgerald, 1989).

Other differences set out in Figure 1 include:

Land Registry Ireland operates on a non-conclusive boundary system, where the map does not indicate the physical feature of a boundary. The physical boundary on the ground is the most reliable evidence of physical features, such as hedge, ditches, fence or wall (Maltby, 2010). Ordnance Survey Ireland (OSi) is Ireland’s official national premier mapping agency and is responsible for the topographic mapping indicating the natural and built environment. The OSi position regarding property boundaries is that,

“OSi maps never indicate legal property boundaries, nor do they show ownership of physical features. Although some property boundaries may be coincident with surveyed map features, no assumptions should be made in these instances and consequently it is not possible to identify the position of a legal property boundary from an OSi map” (OSi, 2011, pg. 1). From research the OSi conducted from 2004 – 2009, accuracy of their large scale mapping system indicates accuracy of urban areas to be 98.7% accurate to within 2m and 99.9% accurate in rural areas to within 5m accurate (Society of Chartered Surveyors, 2010).

(Blog Post added 07/10/2025)

From research the OSi conducted from 2004 – 2009, accuracy of their large scale mapping system indicates accuracy of urban areas to be 98.7% accurate to within 2m and 99.9% accurate in rural areas to within 5m accurate (Society of Chartered Surveyors, 2010).

Under the provisions of the Registration of Deeds and Title Act 2006, the Registry of Deeds and the Land Registry were combined to form the PRA. The Land Registry and Registry of Deeds had been undergoing major changes to its systems for a number of years and a more modernized land registration system was needed, such as digital mapping, to further develop online services such as e-conveyancing. Another reason for this amalgamation was that legal transactions were up by 125% mainly because of the property boom in Ireland between 1999 – 2006 (Organisational Review

Programme, 2008). The PRA’s primary statutory mandate is to provide a system of registration of title to land that is complete and easy to use. According to O’Sullivan (2007),

“…when the title to a piece of property is registered, the PRA on behalf of the State guarantees that title. The statutory position is that a deed does not operate to transfer registered land until the transferee is registered as owner. This means that no legal title passes to a purchaser of registered property until the transaction is registered on the land register” (O’Sullivan, 2007, pg.1).

Approximately 1.8 million registered titles covering about 2.5 million land parcels are now catered for in the Land Register (85% of all legal titles within the state) (O’Sullivan, 2007). The Land Registry in 2005 announced that all existing paper based maps would be converted into electronic form over a five-year period, known as the Digital Mapping Project. In August 2010 the mapping project was completed with all 26 counties fully digitized. The digital mapping project now provides easy access to data, which is viewed by clicking the seed point on the map to give information on the property, including the folio number.

(Blog Post added 20/10/2025)

4. LAND REGISTRATION & CADASTRAL SYSTEMS WORLDWIDE

To put Ireland’s registration system into perspective, one needs to compare it to other systems around the world (Figure 3).

4.1 French System

The French system dates back to Napoleon I where it was used extensively to collect land tax. The system contains maps showing location of boundaries of all land units. It is based on a deeds system of registration where titles are not guaranteed by the state.

4.2 German System

The German system is based on title system of registration where registered titles are guaranteed by the state. It has a fixed boundary system based on cadastral surveys.

4.3 Torrens/English System

The Torrens system uses fixed boundaries based on Cadastral surveys where registered titles are guaranteed by the state (Brophy, 2003). The English system is a variant of the Torrens system of land registration, where registered titles are guaranteed by the state, however boundaries are not. Properties are identified on maps from Ordnance Survey maps using general/non–conclusive boundaries.

(Blog Post added 20/11/2025)

Recording boundaries accurately is not just a problem here in Ireland. It is an issue worldwide. In Hong Kong, official monuments may mark the corner of land parcels, while boundaries may be defined by descriptive plans however it may not fully define boundaries on the ground (Park, 2003). In Hong Kong, Tang (2004) describes their land registration system as way behind the stable Australian boundary system and very far behind the Singaporean system, where their national land boundary records are a legal co-ordinate cadastre.

Land administration systems are essential parts of a country’s national infrastructure. They are in constant reform and are part a nations identity,

“…representing societies perceptions of land, making them distinctly different in every country… Land administration systems are generally complex in themselves, and the cultural, traditional, and social diversities increase the complexity of evaluating and comparing national systems with each other even more” (Steudler, 2004, pg. 4)

Land registration systems are all well and good for countries that can afford them, it is different in third world countries that have no funding and cannot afford such elaborate systems. This can be seen primarily in South America where they have adapted deeds registration without legal sanction of boundaries (Tang, 2004). A main contributor to the cause of property rights for poverty stricken countries is Peruvian born economist, Hernando De Soto. De Soto (2000), describes England & Europe as having “an integrated legal property system” that manages a nations assets. Europe with their Cadastre and England with their title based system enables these countries to register land effectively. De Soto wants more security of tenure for property owners in undeveloped countries. De Soto has acted on this and has proposed that land held by the poor be titled, and thus create financial opportunities that would release the value of land. De Soto believes that this would help identify capital that is tied up in land and use their land as security and an opportunity to access credit. This ideology is now being implemented by the United Nations (Williamson et al, 2010).

(Blog Post added 09/12/2025)

5. SOCIAL BOUNDARIES

However, for the undeveloped countries, access to credit is not as important as the way they value their land. The same is for western democracies. People value land for spiritual, social, & economic reasons, it is not just something people walk on (Williamson et al, 2010). Irish people for instance, have had a long affection with land and Irish boundaries and boundary disputes have been famously depicted in literature and film. This connection to land has been highlighted by Patrick Kavanagh in his 1938 poem, “Epic”, which described a violent row between neighbours.

“…who owned/that half a rood of rock, a no-man’s land/ Surrounded by our pitchfork-armed claims./I heard the Duffy’s shouting “Damn your soul…” (Brien el al, 1972, pg. 136)

More recently the 1990 Hollywood movie, “The field” was written by John B. King as a play in 1965, featuring “The Bull McCabe” who did all he could to save (murdering the purchaser of the land) the land he loved from being sold at public auction. What is impressive about “Epic” and “The field” is the timelessness of the writing. They both continue to be applicable in modern Irish life and have not lost relevance in the years of writing where one witnesses land and boundary disputes cases in the courtrooms of modern Ireland.

(Blog Post added 16/12/2025)

CONFERENCES & PRESENTATIONS

PEER REVIEWED

- O’Brien D & Prendergast WP, (2013) Why area Property Boundary Disputes increasing in Ireland? International Built Environment Postgraduate Research Conference, Manchester, 8-10 April 2013.